It's becoming more and more clear, on many levels, that we have gone

far beyond what wisdom would suggest as the limit of forest exploitation

in New England. Early European settlers faced daunting challenges upon

their arrival here, having known only a homeland that had already

largely exhausted its forest cover. The magnificent timber they encountered on these shores was

seen not only as a fabulous, infinite resource, but an imposing

wilderness that had to be defeated, cleared, and replaced with crops.

Had

we been in their shoes, we no doubt would have felt the same; it was a matter of survival. But we

are now long past those days of "opening up the land for farming," and of homesteading and back-breaking travails. We see that, in establishing this

country, we've been overzealous in our conquests, and maybe we

should apply a bit of restraint. Forest cover has returned to a large

extent in New England, and we have mostly stopped clear-cutting. However, we

still operate on the theory that we can continually cut trees that have

reached the ripe old age of 60 or so years, and that that is

"sustainable".

Early Successional Forests

But now there is weighty pressure today, at

least in Massachusetts, to once again remove a significant percentage of

our more "mature" forests (which, in biological fact, have barely reached their

adolescent years) to create more early-successional habitat, from

grasslands to young, small-diameter trees.

Why? Such conditions favor several

game species (deer, turkey, rabbits, some bird species, etc), which sounds

attractive. And it actually is attractive habitat, which I've always

enjoyed. But there is no shortage of deer, turkey, and rabbit here. In

fact, they've become nuisances in many suburban locales.

|

| Early-successional habitat |

|

|

The Biomass Scheme

Even far more disturbing is the latest money-making bonanza: burning wood on an industrial scale, aka "biomass". The proponents of this ill-conceived plan state that this is a wonderful, sustainable, green, carbon-neutral way to generate energy and deal with the climate change issue. They have, in other states to the south and west, promised that they would burn (and/or make wood pellets from) only the "waste" wood that is a byproduct of logging (ie, poor quality trees; and branches, bark, sawdust, etc). Sounds like a good idea, doesn't it? If that's your reaction, you owe it to yourself to see a film on the subject as soon as possible... "

BURNED: Are Trees the New Coal?".

|

| "There was a forest here last week..." |

I

saw the film recently, and I can promise you it will change your mind about supporting the biomass industry. What has been done to forests and people in the southeast and upper midwest is unconscionable, and about as far from "green" and "sustainable" (whatever those terms mean), and carbon-neutral as one can get. Would you suppose that burning old creosote-soaked railroad ties and tires (to the tune of thousands of tons at a time) is a good practice? Is it advisable to level entire forests and burn every pound of woody matter that once was tree? Furthermore, the wood pellets being produced from our razed forests are mostly being shipped to other countries around the world... we're destroying our natural environment so that foreign countries can benefit at our expense.

That's what has occurred in other states. It may not go to that extreme in New England states. But once an industry and infrastructure are in place to make pellets and burn wood, do you suppose there would be enough "waste" wood to keep them going indefinitely? Or is it likely that, before long, whole trees and forests will be on the chopping block for furnace fuel?

It is known that burning wood, especially on an industrial scale, pumps much more carbon dioxide into the atmosphere than burning coal or fossil fuels. That will only exacerbate the greenhouse gas effect that worsens climate change. At the same time, the forests that had been actively removing carbon dioxide from our air by locking up carbon in their trees and soils would be removed, thereby making the problem even worse.

The claims made by the forestry industry that young, vigorously growing forests sequester the greatest amounts of carbon (thereby removing carbon dioxide from the air) sound plausible. Trees produce wood, and wood is largely composed of carbon. So, it seems to make sense that a rapidly growing young forest, such as you'd see regenerating after a cut, would be packing carbon away in the new trees: you can easily see that a whip of a sapling has grown several feet in height in a year in some cases. And it's true, those trees do sequester carbon in their wood.

Bigger is Better

But what's not broadly understood is that

large, older trees are much more productive in that regard, and are laying down far greater amounts of wood in their massive trunks, limbs, and roots. They have huge crowns of foliage that are photosynthesizing a much greater amount of sugars than a sapling or small tree can, and that's what is packing carbon away for long term storage.

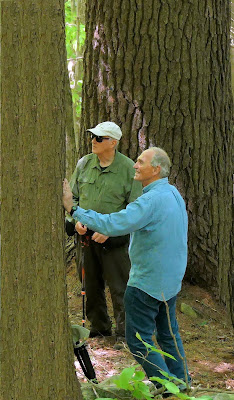

|

| Which do you suppose stores more carbon: young forest... |

|

| ... or old ? |

|

It may not appear that big trees are growing as much as young trees are, because their new growth is mostly occurring way up under the lofty crowns, where the old trees are putting on girth at a greater rate than in their lower trunk (the greatest amount of growth takes place just under the crown, where the most photosynthates are available from foliage).

Think of the shape of a tree trunk... it tapers down toward the top of the tree, like a cone. As years go by, the trunk thickens, and grows taller. Eventually, a maximum height is achieved, but growth still happens: the upper regions of the trunk increase in diameter more than the lower region, and the trunk becomes more columnar than tapered. Carbon is still being drawn from the air and converted to wood tissue, just more so toward the top of the trunk. And because of the large circumference of the trunk (and limbs, roots), a greater absolute amount of wood is being created in the large old tree than in a puny young tree. It's that simple.

The Felling-for-Furnace Folly

Cutting down a forest to burn its wood, then claiming that the regrowth of that forest counterbalances the carbon emissions is pure folly. The burned wood puts carbon dioxide into the air, and it will take decades or centuries for the regenerating forest to recapture that carbon. It's like scrapping a car and melting the steel down to be recycled. Yes, a new car can eventually be made from the metal, but in the meantime, you still don't

have a car! Plus, the cut forest no longer produces oxygen.

Forests (and oceans) are by far the best tools for removing carbon dioxide gas from our atmosphere. They are absolutely essential to life on this planet, maintaining a life-supporting balance of gases in our atmosphere.

Old Growth Forests

Rather than more young, early-successional forest, what we sorely need is much more old growth forest. That could come about by designating as "no-cut" some percentage (or

all) of the maturing public forests we currently have. Many of those second-growth forests are over a century old now (but not yet old growth). They are highly valuable as carbon sinks, and should be left completely unmanaged, to become old growth once again, just as nature had been doing for eons before we got here.

That's what's

missing from our environment: old, natural forest. And I don't mean park-like

stands of 75-year-old trees, and certainly not monoculture plantations. I mean true old-growth forest, where natural processes take place, unhindered by humans. It will take strong public will to allow nature to carry on its timeless work, but it can, should, and must, be done.

Old growth forests have many benefits besides carbon sequestration. They are unmatched at providing clean water. They filter pollutants from the air, and are oxygen factories. They maintain the genetics of trees that have survived and persisted through varying conditions for centuries, assuring adaptability to fluctuations in climate, to imported diseases and pests. They prevent erosion of soils into our waterways, and mitigate potential flood events. They create macro- and micro-habitats that foster a great diversity of life forms not found elsewhere. Their soil-borne

mycorrhizal fungi networks interconnect trees and plants, greatly improving the health and viability of all those connected members. And, not least of all, they beckon to our human spirit; we intuitively know that "all is well" when we immerse ourselves in nature's holiest of places.

|

| Moss-covered Old-Growth Sugar Maple |